Project

The scientific work for the DISCONNECT is organized in three work packages (WPs). In addition to the work on these three WPs, we also work on methodological deliverables and output that spans across the different WPs. Below, we explain these efforts further.

Work Package 1: A digital ethnography of digital disconnection interventions and the discourse surrounding commodified disconnection

The first WP (completed) entailed a digital ethnographic study of products and services that aim to support digital well-being, and the media discourses surrounding them. Two classification frameworks were developed: The first framework classifies interventions according to what they consider the root cause of the problem. Using the drug, demon and food metaphors, our analysis identified three root causes, namely the individual susceptibility to become addicted to digital media (media as a drug), technologies being designed-for-attention (media as a demon), and a poor fit between an individual, the context and a respective media diet (media as a food). This ‘drug, demon, donut’ classification was published in 2022 in Current Opinion in Psychology and has already garnered over 40 citations. You can find the publication here.

| Social Media as… | a Drug | a Demon | a Donut |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is at stake? | Addiction/health | Distraction | Well-being |

| Root cause of problem | Individual susceptibility | Addictive design | Inadequate fit |

| User agency | Agency is limited due to innate susceptibilities | Agency needs to be reclaimed from social media platforms | User has agency, but it is challenged by person-, technology- and context-specific elements |

| Focus of disconnection | Complete abstinence, re-training of the ‘faulty brain’ to break the dopamine link | Removing/weakening the distracting potential of tech, using persuasive design to support exerting social media self-control | Disconnection interventions tailored to persons and/or contexts to ‘optimize the balance’ between benefits and drawbacks of connectivity, mindful use |

| Digital disconnection examples | Digital detox, cognitive behavioral therapy | Muting phone, disabling notifications, putting phone in grey-scale, using apps that reward abstinence (e.g., Forest) | Locative disconnection, disconnection apps that extensive tailoring to persons and contexts, mindfulness training |

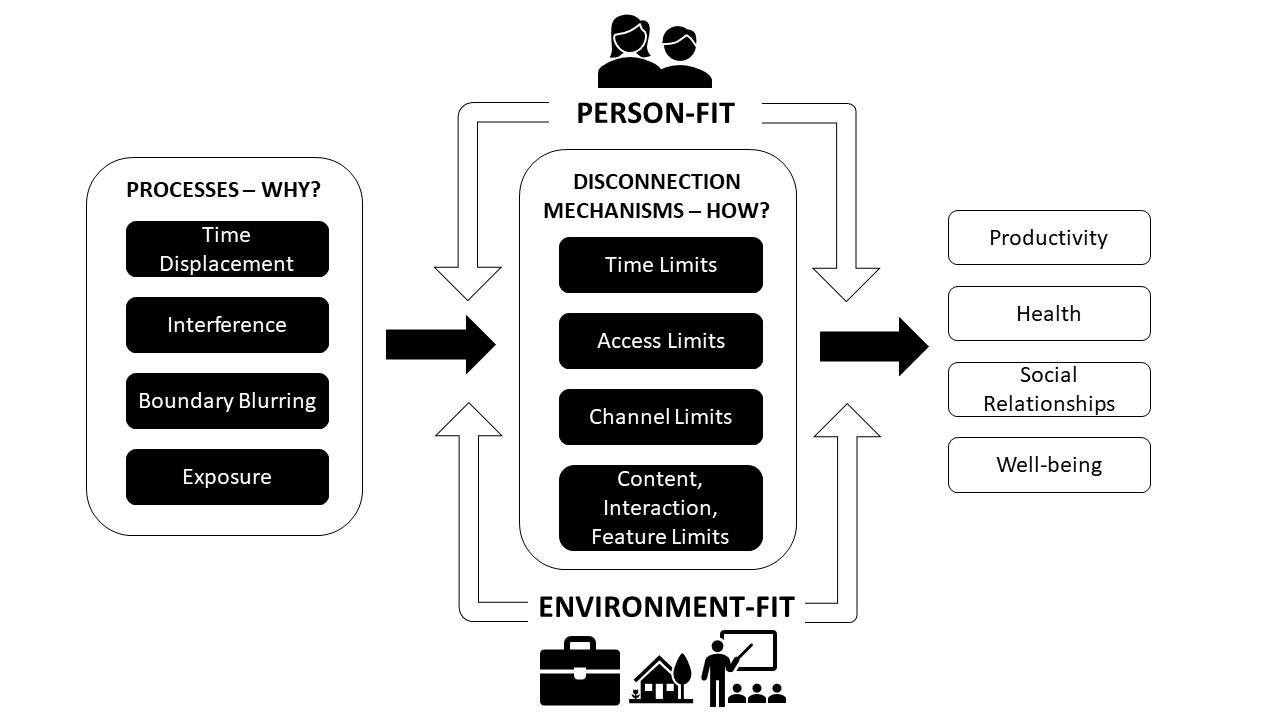

The second classification framework identifies six digital harms that interventions might attempt to mitigate: time displacement, interference/distraction, boundary blurring and exposure to undesirable contents, interactions and features. Currently intervention research is inconclusive about the effectiveness of digital disconnection. To overcome the current status quo of ‘mixed evidence’, we argue that applied research on interventions should make explicit which harms the intervention intends to mitigate and what proximal mechanisms are relevant to that harm. This framework is publication in Communication Theory. You can find the publication here.

Finally, we performed a discourse analysis of marketing communication on digital well-being products and services. This analysis, published in Convergence (2023), showed that marketing discourse presents digital disconnection as an individualized responsibility to (re-) gain control, focus and productivity; The burden of this responsibility appears unevenly distributed as discourse reproduces stereotypical gendered caring roles. Thus, not everyone is deemed equally responsible to care for disconnection. You can find this publication here.

Work Package 2: A longitudinal ethnographic study of adults’ digital well-being experiences

WP2 entails a longitudinal digital ethnographic study, in which we examine how digital well-being and digital disconnection unfold in everyday life. We recruited, interviewed and observed a select group of adults, with varying backgrounds, over a longer period. Crucial to the ethnography is that we perform ‘follow-along’ observations: We accompany our participants as they move through their everyday life, joining them in the early morning as they prepare themselves and their children for the day, going to work with them, and being present during their hobbies/social activities. Combined with both formal and informal interviews, this approach enables us to witness how digital well-being unfolds and manifests in the concrete experiences of individuals.

The work on WP2 has revealed that individuals experience social, material, and individual obstacles experienced in day-to-day life that hinder and foster their digital wellbeing. By putting forward a relational approach, our work makes visible how these obstacles are interrelated, and can be situated against gendered responsibilities and other (unequal) social relations. From this study, we developed the concept of ‘repressed agency’ to acknowledge how individual agency is consistently constrained and dependent. Several manuscripts are prepared on the work performed in this work package.

Work Package 3: A longitudinal measurement burst study.

In WP3, we collect (1) experience sampling data, (2) longitudinal survey data, (3) smartphone log data and (4) computer/laptop data, and use these data to test complex models of how digital well-being experiences affect health and well-being.

For this work package, we therefore a collaboration with large local newspaper, De Standaard, and organized the study in the form of a citizen science project, known as the On/Off project [On/Off Onderzoek]. More details about the citizen science project can be found on www.destandaard.be/onoff.

We collected survey data from more than 1400 adult individuals (i.e. almost double of our already ambitious aim). These individuals contributed over 67.000 experience sampling questionnaires, and more than 7 million unique smartphone/computer use events. The impressive - and to our knowledge unprecedented - size and scope of the dataset allow to capture the dynamic nature of digital well-being experiences, and to test the various pathways linking these experiences to various short- and longer-term indicators of health and well-being such as fatigue (precursor to burnout) and mood (precursor to depression. For instance, we published a study on the phenomenon of ‘mindless scrolling’ on social media, showing that this behavior elicits a guilt response in individuals which eventually negatively affects their end-of-day affective well-being. The publication of this study can be found here. A second study reveals that the feeling of being ‘always on’ and under pressure to be so elicits mental fatigue in individuals, and that this effect lingers, remaining noticeable up to 6-8 hours later. We hope to publish this study soon.

Methodological deliverables

In addition to the work performed to carry out the above work packages, we are also working on several methodological deliverables (manuscripts/deliverables in preparation). These include a manuscript on the going-along method used in the ethnography, a manuscript on the use of cross-device data in research, and a manuscript on the use of R Markdown for generating individualized reports for participants.

Scientific deliverables spanning the project.

We also work on deliverables that reflect on the field of research. Two examples of such deliverables are the article that we wrote as Editorial for the special issue of Mobile Media & Communication on “Digital Well-being in an Age of Ubiquitous Connectivity” and the article that Sara Van Bruyssel co-wrote together with several other junior researchers in the community, a collective that goes by the name, the ‘discollective’. This article is titled “Mapping a Pluralistic Continuum of Approaches to Digital Disconnection” and was published in Media, Culture and Society. You can find these on our publications page.